the dive site...

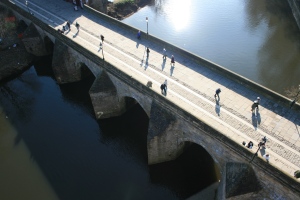

Elvet Bridge, Durham, a multi-period underwater archaeological site.

The find site, positioned just downstream of the twelfth century Elvet Bridge in Durham City, lies mid-way between two areas of late-medieval urban development:

the Borough of New Elvet and the Bishop's Borough. The late-medieval city of Durham comprised of five boroughs, the tenements located in the Bishop's Borough,

positioned immediately to the west of the find site, were known as Saddlergate (now Saddler Street), while the tenements which abut the river to the east

(in the Borough of New Elvet) were simply referred to as Elvet Bridge End or Bridge End. Previous archaeological excavations in these New Elvet and Saddler Street

locations (Carver 1974 and 1979) suggest that the property boundaries of these tenements survived until the late-twentieth century. The chronological period of

study of the DRWA effectively mirrors the development of these two boroughs from the thirteenth through to the early-twentieth century. Although the majority of

the objects can be dated to a period of use between the Tudor and Stuart periods, many can be ascribed to an earlier time which coincided with the main period of

the urban development outside the peninsula's fortified walls following the construction of Elvet Bridge in the twelfth century. Initial dating has come from

analysis of a selection of coins, and a few typologically distinct artefacts. An accurate picture of the range of material and its distribution over time must

await detailed cataloguing and analysis. Comparable assemblages may be imagined to exist in the riverbed of every city with a major river in Europe.

Egan (1998, 12) has shown that objects, excepting deliberately curated heirloom objects, are normally discarded within a generation of their manufacture,

thus this continuous 'random' sample can also be explored as an assemblage describing the changing social tastes, methods of manufacture, interests and activities

of the people of Durham across the period of the thirteenth to twentieth century, so providing a rare physically evidenced picture of the change for the medieval

to modern world.

The find site, positioned just downstream of the twelfth century Elvet Bridge in Durham City, lies mid-way between two areas of late-medieval urban development:

the Borough of New Elvet and the Bishop's Borough. The late-medieval city of Durham comprised of five boroughs, the tenements located in the Bishop's Borough,

positioned immediately to the west of the find site, were known as Saddlergate (now Saddler Street), while the tenements which abut the river to the east

(in the Borough of New Elvet) were simply referred to as Elvet Bridge End or Bridge End. Previous archaeological excavations in these New Elvet and Saddler Street

locations (Carver 1974 and 1979) suggest that the property boundaries of these tenements survived until the late-twentieth century. The chronological period of

study of the DRWA effectively mirrors the development of these two boroughs from the thirteenth through to the early-twentieth century. Although the majority of

the objects can be dated to a period of use between the Tudor and Stuart periods, many can be ascribed to an earlier time which coincided with the main period of

the urban development outside the peninsula's fortified walls following the construction of Elvet Bridge in the twelfth century. Initial dating has come from

analysis of a selection of coins, and a few typologically distinct artefacts. An accurate picture of the range of material and its distribution over time must

await detailed cataloguing and analysis. Comparable assemblages may be imagined to exist in the riverbed of every city with a major river in Europe.

Egan (1998, 12) has shown that objects, excepting deliberately curated heirloom objects, are normally discarded within a generation of their manufacture,

thus this continuous 'random' sample can also be explored as an assemblage describing the changing social tastes, methods of manufacture, interests and activities

of the people of Durham across the period of the thirteenth to twentieth century, so providing a rare physically evidenced picture of the change for the medieval

to modern world.

The discovery of these artefacts has created a unique evidential resource. Unlike traditional archaeological sites, where sporadic specific deposition events at a particular location and time lead to an absence or over representation, the river has been constantly sampling the material culture of Durham throughout its period of occupation. The biasing effects of the flow of the river, oxygenated water followed by deposition in anoxic silt have been constant throughout this time, everything which was washed, dropped, thrown or fell into the river was potentially sampled, providing an assemblage of the small heavy objects which fill people's lives.

After its construction, Elvet Bridge soon became a vital link between the commercial centre of medieval Durham and the surrounding countryside, countless artisans,

merchants, freemen, and pilgrims would have crossed the bridge on a daily basis; it was the potential for exploitation of this passing trade that encouraged pedlars

and vendors, with Bishop's consent, to build various shops, booths and bothys on and off the bridge superstructure. Although several objects recovered from the

find-spot can be linked to Durham's medieval agrarian-based communities located outside city walls, there are many examples of objects that link directly to the

nineteen occupations mentioned in the Durham Priory deeds, account rolls and rentals that were in existence in Durham from the late-fifteenth century (Bonney, 1990).

By far the largest quantities (by typology) of objects in the collection are dress accessories; there is textual evidence that these objects were once offered up for

sale to the passing trade on Elvet Bridge. These typically small metal finds include objects such as, buttons, buckles, pins, decorative and figurative mounts, eyelets,

strap ends, chapes (or aglets) and brooches. Objects associated with the evolution of trade and industry are also present, for example, lead trade weights and lead tokens,

coin weights (for gold coins), seventeenth century copper trade tokens, jetton and hammered silver coins; while a substantial lead cloth seal collection (346), the largest

available for analysis outside of London, reveals for the first time tantalising material evidence of the trade, industrial regulation and taxation of commercially produced cloth.

Leather, wood and metal working tools are present together with various ingots and casting waste - likely evidence of local manufacture. Objects relating to the

domestic household such as butchered animal bone, window came, toys, pewter spoons, knives, security equipment, floor tiles and medieval ceramics, including glazed

ware reveal much of the day to day life in the lower echelons of society. Several types of round shot, made from lead, iron and stone, hint at periods of conflict

throughout Durham's past. Evidence of late-medieval pilgrimage, for example, lead ampullae, pilgrim signs, including the first example of a pilgrim badge in the

form of a small pewter Cuthbertine pectoral cross, medallions and other mounts symbolic of Christian pilgrimage are also included.

After its construction, Elvet Bridge soon became a vital link between the commercial centre of medieval Durham and the surrounding countryside, countless artisans,

merchants, freemen, and pilgrims would have crossed the bridge on a daily basis; it was the potential for exploitation of this passing trade that encouraged pedlars

and vendors, with Bishop's consent, to build various shops, booths and bothys on and off the bridge superstructure. Although several objects recovered from the

find-spot can be linked to Durham's medieval agrarian-based communities located outside city walls, there are many examples of objects that link directly to the

nineteen occupations mentioned in the Durham Priory deeds, account rolls and rentals that were in existence in Durham from the late-fifteenth century (Bonney, 1990).

By far the largest quantities (by typology) of objects in the collection are dress accessories; there is textual evidence that these objects were once offered up for

sale to the passing trade on Elvet Bridge. These typically small metal finds include objects such as, buttons, buckles, pins, decorative and figurative mounts, eyelets,

strap ends, chapes (or aglets) and brooches. Objects associated with the evolution of trade and industry are also present, for example, lead trade weights and lead tokens,

coin weights (for gold coins), seventeenth century copper trade tokens, jetton and hammered silver coins; while a substantial lead cloth seal collection (346), the largest

available for analysis outside of London, reveals for the first time tantalising material evidence of the trade, industrial regulation and taxation of commercially produced cloth.

Leather, wood and metal working tools are present together with various ingots and casting waste - likely evidence of local manufacture. Objects relating to the

domestic household such as butchered animal bone, window came, toys, pewter spoons, knives, security equipment, floor tiles and medieval ceramics, including glazed

ware reveal much of the day to day life in the lower echelons of society. Several types of round shot, made from lead, iron and stone, hint at periods of conflict

throughout Durham's past. Evidence of late-medieval pilgrimage, for example, lead ampullae, pilgrim signs, including the first example of a pilgrim badge in the

form of a small pewter Cuthbertine pectoral cross, medallions and other mounts symbolic of Christian pilgrimage are also included.